(See my Epstein bibliography for superscript page references. The superscript ‘B’ indicates a reference to the bibliography in general.)

R. Yudel’s life is described in his own words in his introduction to Minhat Yehuda4, and (up to the time of her marriage) by his daughter Pauline in her memoirs. These leave a few large gaps that I have attempted to fill. I address some of them here, and some in my post on his second wife.

The marriage of Yudel and Zelda

R. Yudel’s son Ephraim writes523 of his father that he married at age 14 (typical for the elite of the time) to his wife who was a year younger than he. We are not given any other information that could determine his date of birth (except for Ephraim’s claim that Yudel and his father Zimel lived to about a hundred, which I have shown to be a mistake in part 1 of this series).

Of Yudel’s wife, we have detailed descriptions of her appearance and nature, from her son’s and daughter’s respective writings, but they do not even mention her nameM1:8 (which we learn only from Yudel’s Minhat Yehuda4: Zelda) or any specifics on her background. Ephraim mentions knowing of two of her brothers,523 but seems not to have been familiar with her side of the family.

With what we know, however, we can identify Yudel’s family in the revision lists, the census-like registers made for purposes of taxation in the Russian Empire, for the city of Babruysk, now Belarus (where the Epsteins first lived1:2) via the JewishGen Belarus Revision Lists database.

There we find in 1850 (corresponding to the 9th revision; petty bourgeoisie, no. 567): Yudka Epshteyn son of Zimel’, age 52, 36 in the last count; Zelda (50) daughter of Khaim, his wife; his son Afroim (7 in the last count, ‘missing’ since 1849); his daughter Pesya (19); his son Abram (14, newborn [sic] in the last count).

Confirming that these are ‘our’ Epsteins, there is a corresponding revision list from 1858 (10th revision; petty bourgeoisie, no. 424), containing much less information, listing only Yudka son of Zimel Epshtein (age 52 in last count) and his son Abram (age 14 in the same), noting that they are ‘honorary hereditary citizens’, a class which exempted them from the taxes the revision lists were meant to calculate. We know that Zimel (and, naturally, his heirs) were granted this privilege, as mentioned by Pauline1:9 and as found with Ephraim (in his naturalization petitions, in which he renounces this rank, see the first post), and as inscribed in Polish on the tombstone of Yaakov Michel Epstein, another grandson of Zimel’s (Warsaw, Okopowa St., sector 1, row 5, no. 2; see ibid.), or as can be found in the vital records of the family of Eizik Epstein of Vilnius (Yaakov Michel’s half-brother) in JewishGen’s Lithuania database. (See also below for a rendition of this title in Hebrew.)

Thus we have Zelda’s father’s name as Chaim; further, from Ashkenazi naming rules (which forbid a child to share a name with a living ancestor) we see that he died no later than around 1845, when a child with that name was born to his granddaughter, the wife of Shmuel Feiges (about whom see the first and last posts in this series).

(I will return to the names of the children mentioned in the 1850 revision list in the following post; immediately obvious is the mention of Ephraim, who left for America in 1849, as he writes.524)

A record engraved in silver

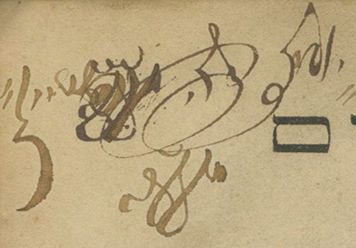

An unexpected find sheds further light. Rather than the usually paper (reproduced digitally or photographically), here we have a marriage record of sorts engraved in silver.

In the catalogue of Kedem Auction House of Israel’s Online Auction no. 17, which took place in December of 2018, we find (item 393; p. 102 in the PDF version of the catalogue, without images) a silver holder for two cruets, engraved on one side with the words ת׳ק׳ע׳ה׳ יודיל הלוי עפשטיין (‘[Hebrew Year 5]575, Yudel haLevi Epstein‘) and on the other with זעלדע ב׳ הרב ר׳ חיים קריינין (‘Zelde, daughter of the Rabbi R. Chaim Kreinin‘).

(Credit: Kedem Auction House, via Bidsprit.com; low resolution version used for fair use.)

These were identified by the auction house staff as being made for the wedding of the parents of Pauline Wengeroff of memoir fame, though without noting the genealogical novelty of this find. (If you follow Epstein family genealogy online, you may have seen these images – and Zelda’s maiden name – on Geni.com. I am not plagiarizing the work of he who submitted that; rather, I am he.)

With the above, we can identify more instances of Zelda’s father’s name or maiden name in the vital records (which we might have not recognized for what they were previously), as will be seen in the next post.

With a date for their wedding (ca. 1815), we now have Yudel and Zelda’s approximate years of birth, by subtracting the ages Ephraim reports for them, 14 and 13; thus these are 1801 and 1802, respectively, consistent (well, as consistent as we can expect) with the revision lists cited above.

Here begins an era of Yudel and Zelda’s life that is relatively well documented (if we ignore the utter confusion regarding the number and identity of their children, to which the next post is dedicated), and I redirect your attention to the entire first volume (and some of the second) of Pauline Wengeroff’s memoirs.

The restless body of a scattered soul

From Pauline’s marriage and relocation to Konotop, her in-laws’ town, our information about her parents becomes sparse; she never again lived close to her parents. The best source onward is R. Yudel’s own account, cryptic though it is, in the introduction to his Minhat Yehuda4, in 1877. Here he describes his life in chronological order – his childhood and education, his time in Brest, his first period of financial success, and the first downturn. But after mentioning the publishing year of his first work Kinmon Besem (1846, still covered by the Memoirs), his more detailed account begins with the time of his father’s death, which we know to be 1854, leaving a gap of several years.

We can fill this gap by searching for mentions of R. Yudel in literature of his time (rabbinic and otherwise), which hint at his wanderings then and beyond, and tell us of his associations with his contemporaries – who cited him, for what purpose, who sought his approbation, whose books did he want, which religious or secular works did he read? These can give us an estimation of where he fit in in the increasingly polarized Orthodox Jewish society of the 19th century, complementing our image of him due to his daughter Pauline, and the difficulties they present.

Firstly, some ambiguities that need to be addressed: there are many references to a Yehudah or Yudel Epstein of Babruysk in the 1860’s and 1870’s, long after our Yudel left Babruysk, which I assume are references to one his numerous cousins in the area, of uncertain relationship. [Update: for a non-rigorous treatment of his possible ancestry, see my Twitter thread on the subject; thanks @Yeshevav et al.] There are also references to our Yudel, throughout his life, as ‘R. Yudel Epstein of Warsaw’ – these may be shorthand for ‘son of Zimel Epstein of Warsaw’, as they date before Yudel’s presumed move to Warsaw.

The latest reference to Yudel in Babruysk which is reasonably identified as him is in 1834, as a subscriber (prenumerant) of a Yiddish textbook of the Polish language, Grammatyka Polska […] by Asher Lemel (Leyman) Mejerson, also known by its Hebrew title, שפה ברורה או תלמוד לשון פלאניא. (Compare this with Magnus’ discussionM2:176n24 of whether Yudel would have let his sons study foreign languages.) I assume the subscription list was compiled a year or two prior to publication, before Yudel moved to Brest. For an unambiguous mention of Yudel and his brother David in Babruysk, both as sons of Zimel Epstein, see the prenumerantn in the Vilna 1833 edition of Avot of Rabbi Nathan with the commentary of R. Eliyahu of Delyatichi.

By 1836, he already appears in Brest as a prenumerant of פרדס החכמה Pardes haHokhma, the homilies of R. Moshe b. Aharon of Salant.

In the early 1840’s, we find him in Brest, as a correspondent of Yitzchak Ber Levinzon (Isaac Baer Levinsohn, ‘Ribal’), the prominent Haskalah leader, whom he addresses as a friend: see Levinzon’s collected correspondence, באר יצחק Be’er Yitshak (Warsaw, 1899: pp. 52–55 (1840), 57–58 (1840), 109–110 (1844), 127–134 (1845, includes Levinzon’s response); also, one mention by Levinzon in a letter to Avraham Ber Gottlober in 1842 (p. 103), referring to correspondence with Yudel four years prior, i.e. ca. 1838). From these we learn that he was, by association, closely connected to the Lithuanian Haskalah, yet from his correspondence we see that ideologically he was Orthodox, condemning as heretical the Galician maskilim Bloch and Mieses and insisting (while asserting that he is not at all a kabbalist himself) on the authenticity of Kabbalah and the Zohar in particular. (Yudel’s discussion of the tanna Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai as possibly a naturalist and entomologist is interesting in light of his wife’s reaction to their son-in-law David Ginzburg’s early-morning research expedition to the yard, as recorded by their daughter Pauline1:131–133.)

Another maskilic publication hinting at Yudel’s time in Brest is Benjacob and Lebensohn’s edition of the Tanach (which included Mendelssohn’s commentary in earlier volumes), specifically volume משלי Mishle, published in 1853, where Yudel’s eldest sons-in-law David Ginzburg and Shmuel Feiges (see the following post) appear as prenumerantn in Brest; Yudel himself does not appear in that list.

Yudel still lived in Brest as late as 1855, when his daughter Pessel, later Pauline, was married in Konotop to Chonon Wengeroff; from there his movements become vague, see my discussion below in my analysis of Yudel’s autobiographical account. There are still several other literary mentions of his that deserve analysis here, though.

In שמן ששון Shemen Sason (Vilnius, 1859) by R. Yitzchak Sason (also spelled Soson) of Horodno (Grodno), we find the de facto approbation of ‘the honorary citizen’ (האזרח הנכבד) Yudel, son of Zimel Epstein, of Warsaw (‘of Warsaw’ follows the formula נ״י, which must refer to the living Yudel and not to his already deceased father), on the page following the rabbinic approbations. Yudel signs in Horodno in the summer of 1857, with the cryptic suffix מקק״ב MKKB (or MQQB, if you prefer).

We find this signature format of Yudel’s on several of his possessions, as sold in the 7 February 2017 auction (no. 54) by Kedem Auctions of Jerusalem: see items 309 and 310 (pp. 266–268, in the PDF edition) in their January 2017 catalogue. These are: (1) Yudel’s copy of the 1848 Konigsberg (modern Kaliningrad) edition of עין יעקב En Ya’akov (collection of Talmudic aggadot) with the commentary עין אברהם En Avraham by R. Avraham Schik (this is the same work to which Yudel’s own Kinmon Besem was often appended to); (2) An incomplete set (five volumes out of six) of the Mishnah with the commentary of R. Yisrael Lipschutz, with whom he corresponded (and argued), as he writes in his Minhat Yehuda8 (the comments published there are to Seder Taharot, the volume missing from the auctioned set).

The En Ya’akov bears Yudel’s signature after a poetic inscription, while Tiferet Yisrael has his name alone; both are followed with the cryptic מקק״ב MKKB. The catalogue writers interpret this as meaning מחבר קונטרס קנמן בשם (‘author of the pamphlet Kinmon Besem‘), though in my opinion מק״ק בריסק (‘from the holy community of Brest’) is just as plausible.

The En Ya’akov signature bears a date and place, which the writers read as [5]612 [=1852], Horodno; I believe the correct reading is 5617 [1857], by comparison with his own handwriting. This places him once more in Grodno in 1857; perhaps he lived there for a while, explaining the reference to Grodno in his (?) death record, see below.

His mention in the 1870 edition of Gevurot haAri19 more firmly places him in Warsaw (for his second period of residence, it would seem, see below). Here he is cited for his speculation regarding the origin of the Epstein surname.

As late as 1875, we find Yudel’s recommendation – among the approbations of R. Shmuel Zanvil Klepfisz, then dayan of Warsaw and Rabbi Chaim Elazar Waks of Kalisz and others – to מים חיים Mayim Hayim by his friend, R. Yechiel Michel Luria of Jerusalem. Here too, he uses his MKKB suffix. R. Yechiel Michel cites a Talmudic interpretation by Yudel, in the space left empty on the final page of his work (36a).

The last living mention of R. Yudel I could find, other than his own Minhat Yehuda, is his oft-cited letter (‘מכתב יקר’), from Warsaw, 1876, addressed to his relative Shmuel Yevnin (author of Nahalat OlamimB) an printed as an appendix to סערת אליהו Sa’arat Eliyahu (Warsaw, 1878; pp. 44–48) of R. Avraham the son of the Gaon of Vilna, edited by Yevnin. The letter transmits several traditions about the Gaon and his disciple, R. Chaim of Volozhin – the latter of whom was the teacher of R. Yudel’s teacher, R. David Tevel Rubin of Minsk.

Besides for tracing his movements, and giving us insight on where R. Yudel stood relative to the great rifts forming in Orthodox Jewish society of his time, as I will soon discuss, these references give us an idea of his stature in the eyes of his contemporaries. I find it necessary to stress this because Professor Bernard Cooperman, in his afterword ‘A Life Unresolved’ to RememberingsB, his edition of Pauline Wengeroff’s memoirs, is insistent on portraying Yudel Epstein as mediocre in every aspect of his life: as a businessman, and especially as a rabbinic scholar. Magnus refutes much of what he writes (regarding the latter point) from her interpretation of Yudel and Pauline’s wordsM1:252–255; I think his contemporaries make this point even more clearly. Why print the recommendation of a formerly wealthy, mediocre would-be scholar? Why are his letters quoted so often? I am in no position to judge his scholarship, but Professor AbramsonB is, and he found his work compelling.

Between opposing camps

One point of Cooperman’s that I do accept is Yudel’s being a transitional figure intellectually265. Yudel’s introduction, Abramson’s anthology of his novellae, his letters to Levinzon, all show him to have maskilic interests – the sciences, more literal interpretations of the sacred text – all while fiercely defending tradition, insisting that the ‘stranger’ aggadot may eventually be shown to be literal (a focus he shared with his correspondent, R. Yisrael Lipschutz), and defending the divine inspiration of the Talmud and even of the Zohar.

Yet as the Haskalah progressed, and viewed more as a spiritual danger, there occurred a rapprochement of the Mitnagdim and Hasidim (Provisory note: I need a better reference for this, my thanks for the suggestions, which I hope to examine; for now, see Wikipedia (sorry!): ‘Misnagdim § Winding down the battles‘.). This can be seen, in my opinion, with Yudel himself: in the final decades of his life, after living in a Hasidic-dominated town for some time (see below), he married a woman from a Hasidic family, the widow of a Hasidic rebbe, no less.

This is not to say that he ever left the Mitnagdic ‘Lithuanian’ society he was raised in; according to the historian Avraham Shmuel Hershberg, who knew Yudel in his Warsaw years, he would spend his time in the ‘Lithuanian’ חברה ש״ס (Khevre Shas – Talmud study society) synagogue of ‘Nalevkes’ i.e. Nalewki Street, Warsaw – a Mitnagdic stronghold (Pinkos Bialystok (an edited version of Hershberg’s research), 1949, vol. 1, p. 162; cf. Kotik (cited below), vol 2., p. 55).

“My house, in my field that I bought myself”

Returning to R. Yudel’s chronological account, where he describes the following sequence of events:

- The death of his father [1854], and his inheritance of a portion (unfairly small, he writes) of his father’s wealth

- His success in court, winning him compensation of 80,000 rubles, beginning his second era of prosperity in which “my house was open wide, in my courtyard, in my field that I bought myself, and I wished to live in peace”

- The troubles of Poland in 1862 [i.e. the build-up to the Polish insurrection of 1863]

- The subsequent death of his wife, Zelda

- His second marriage [to Roiza]

- His loss of all his fortune and possessions at the hands of two ‘cruel men’, one from Radom and one from Kozienice

- His subsequent empty-handed move to Warsaw, and his financial reliance on his children from then on

It follows from R. Yudel’s account that he settled somewhere – on land that he purchased – after his father’s death in 1854, and presumably remained there until his defeated relocation to Warsaw, some time after 1862, allowing for time for his first wife’s death, his second marriage, and the financial troubles that lead to his final move. (Confusingly, in the text of Minhat Yehuda483 he makes a reference to his time living in “my courtyard that I inherited from my father”, surely after 1854 – perhaps this occurred before his purchase of his own property?)

Where was Yudel’s ‘house in the field’? As I show in my discussion of Yudel’s children in part 3, his youngest daughter’s marriage took place (or was at least was registered in) Góra Kalwaria (Gur, Ger), a town not far from Warsaw, in 1856. This in itself suggests that he may have lived there.

Furthermore, Yudel often mentions his acquaintances with whom he discussed his studies in his Minhat Yehuda. (See Abramson.B) Most are his childhood acquaintances, from the historically Lithuanian regions of the Russian Empire; many of these, and some of the others, are family members; occasionally he refers to residents of Warsaw. Two references254,443 to associates that do not fall into any of the above categories are both to residents of Góra Kalwaria: the More Tsedek (rabbinic judge) and the ritual slaughterer of the town. This further suggests that he spent some time there.

The death of Zelda

As shown, Zelda’s death belongs to the era of ‘the house in the courtyard in the field’. All our sources – R. Yudel as cited above, his daughter Pauline Wengeroff, and his son Ephraim – are vague as to exact year of her death; the best estimate is between 1862M1:5n29 (the date Yudel gives for the beginning of his troubles) and 1866 (the year of the Italian War, which took place after Zelda’s death2:27).

Hence, we expect to find her death in Góra Kalwaria in that range, and indeed we do (perhaps): on JRI for Góra Kalwaria in 1864 (no. 19), the death of Zelda Epsztejn. (If you happen to have access to these archives, please…?)

Soon after, in R. Yudel’s account, begins the era of his second marriage, to Roiza née Rubin. This belongs to my series on the Rubin family, in particular part 4, dedicated to Roiza’s latter years. There I suggest that their marriage record can be identified in Góra Kalwaria as well, which places them in Góra as late as 1866.

Twilight

At some point, then, misfortune befell R. Yudel Epstein again and he settled in Warsaw with his second wife – near his children, he implies (as will be discussed in the post devoted to them), who cared for him financially, while relying on his younger wife for her assistance in his daily life as he grew older.

In 1877, with his children’s funding, he finished the publication of his project of 40 years, his Minhat Yehuda. His younger brother David had died some five years prior (a Talmudic insight of his from his final days is cited therein), and Yudel himself would die less than two years later, in 1879. (While he thanks his sisters, generally, he pointedly does not thank any brothers, despite the fact that at least one of his half-brothers in Warsaw still lived: Pinchas, see part 1. I imagine this is related to the dispute over his father’s inheritanceM1:255, hinted to in his introduction, and as reported in the memoirs of Yechezkel Kotik, מיינע זכרונות Mayne Zikhroynes (Berlin, 1922; vol. 2, p. 52; see also the digitized version of David Asaf’s Hebrew edition, f.n. 120), whose uncle, the dayan R. Yehoshua Segal of Warsaw, arbitrated the resolution. In contrast, David is mentioned warmly in Minhat Yehuda.)

Professor Magnus has only an approximate date of death, 1879–80;M1:4 this omission is surprising, as the precise date has been available even in English-language reference works for more than a century. At the end of its entry on Warsaw, The 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia has a list of notable Jewish citizens, among them (under ‘Scholars’): Judah b. Zimel Epstein (d. Oct. 7, 1879), author of “Minḥat Yehudah”, reproducing Nahalat Olamim (§14577), the source for the entire list. In modern times, I direct you the digitized Warsaw Okopowa Street Cemetery (sector 1, row 6, no. 3).

“The firstborn son has entered”

Even in death, R. Yudel had the last word: behold his tombstone!

(Credit: the Foundation for Documentation of Jewish Cemeteries in Poland)

The wording, as the epitaph informs us, is of R. Yudel’s own choosing; it certainly is not formulaic like its neighbours.

‘The firstborn son has entered to his father, to the right’, R. Yudel says, which while literally descriptive – Zimel is buried between his two eldest sons, Yudel to his right and David to his left – also echoes the language (יכנס בן אצל אביו ‘may the son enter to his father’) of the Talmudic story (B.M. 84b, q.v.) of the Mishnaic sage whose bier was obstructed by a serpent until that phrase was uttered. Additionally, instead of telling us when he passed (נפטר), the epitaph tells us that he ‘lived until (חי עד)… the 20th of Tishre 5640’.

Absent from Yudel’s phrasing is any mention of his father’s name, or indeed his own full Hebrew name. These are supplemented in the upper inscription, over the declaration that the wording below is Yudel’s own. Yudel instead chose to identify himself as only “H.R. [‘Rabbi’, roughly] Yudil Epstein, author of Minhat Yehuda“.

By far the strangest aspect of his epitaph are the marks over some of the letters, which might be taken for marks of wear or flaws, but his contemporary (and relative) Yevnin, in Nahalat Olamim, says these are deliberate, and according to his wishes: five circular dot-like indentations arranged in an arc over the resh of ה״ר ‘H.R.‘, and a horizontal line over the bet of הבכור haBekhor (‘the firstborn’). Of these, Yevnin writes (and I am paraphrasing) ‘he had his reasons’. (In Yevnin’s description, the second mark has the form of the Hebrew vowel hataf patah (a line with two dots under one end), but I cannot see the dots in the high resolution image provided, nor any sign of wear that would have removed them.)

I am not aware of a precedent for such markings, nor do I have any idea what they might mean. Certainly a mystical interpretation is unlikely; as R. Yudel writes to Levinzon (see above; ibid. p. 110) ולא ידמה ידידי מר שאנכי מהעוסקים בקבלה או מהמתנהגים על פי סוד (‘do not imagine, friend, that I am of those who occupy themselves with Kabbalah or conduct themselves mystically’).

The Hebrew date of death computes to 7 October 1879, as stated; this brings us to a final piece of obscurity about R. Yudel. While death records for Warsaw for that era are not necessarily comprehensive (some districts appear not be in JRI’s database, as of the date of this post), there is a death record that corresponds to Yudel’s – somewhat, and my limited knowledge of Russian doesn’t help.

In the death records for 1879 in the District IV of Warsaw (no. 658; new link), we have Mordka Epsztejn, the son of Zimel and Maryia, from Grodno, died 6 October 1879. If this does not refer to Yudel, we have an odd coincidence. (Though there certainly was a Marka son of a Zimel Epshtein from Grodno, who appears in records in Bialystok, age 24 in 1897, this obviously is not he.)

If you have experience reading 19th-century Russian vital records, please let me know whether the original says anything more than what I’ve copied from the index. (I can discern for myself that Mordka, Zimel and Maryia were copied correctly.)

http://www.ivelt.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=31&t=30192

LikeLiked by 1 person

My grandfather, yes – though not really connected to the subject of the post.

LikeLike